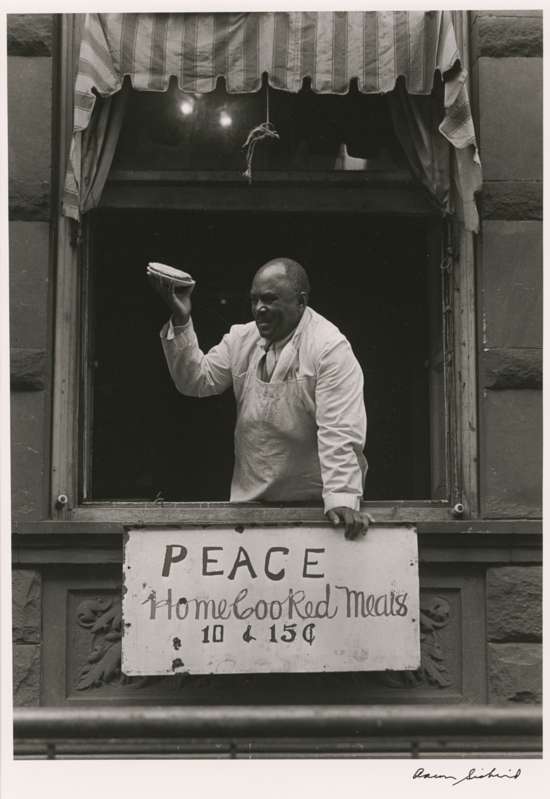

Aaron Siskind, Peace Meals from a Harlem Document

1937

Snite Museum of Art

The job of a photographer undoubtedly presents many difficulties in regard to representation: as a framing outsider, it is an ongoing battle to photograph a subject without aestheticizing them in such a way that highlights the photographer’s own views and culture. Twentieth century photographer Aaron Siskind was no exception. According to literary scholar Sara Blair, Siskind was aware of "a partially shared social landscape, and the history of white looking. . . Siskind probes aesthetic and cultural consequences of the documentary mode (Blair, 32).

Siskind’s efforts in incorporating an awareness of the specific challenges of Harlem as a photographic site "proved a valuable precedent to later African American photographers working to free themselves of the... [burden] of the ongoing imperative to represent race" (Blair, 32). Aaron Siskind was a key player in bringing into contact both black self-representation and white image making, and through this effort, the genre of documentary currently poses open-ended questions about its viewers’ habits of encounter with their own obstructed history (Blair, 32).

Aaron Siskind’s personal development as a photographer began in 1932 through his association with the New York Photo League, which fostered a commitment to creating art that sparked social change and individual growth as artists (Siskind, 14). Many of his colleagues were involved in photographic projects for mass-media magazines, and through these associations, Siskind became aware that every picture is a self-consciously mediated image. Siskind postulated that a photograph corresponds to the perceptions of the photographer, but not necessarily the literal meaning of the subject being photographed.

Many agencies that regularly published Photo League pictures manipulated them in ways that illustrated and enforced racial stereotypes. As this occurred, Siskind and his students strove to make the meaning of their documentary photographs unambiguous (Siskind, 19). I argue that Siskind deliberately chose to aestheticize Peace Meals from a Harlem Document as a strategy to control and command the meaning of his photographic subject. The subject's averted gaze is an indication that his narrative cannot be manipulated by the photographer.

Among the photo series produced by Siskind and his students in response to manipulation of their work, was the Harlem Document, conceived by the black sociologist Michael Carter. Carter proposed that the Photo League collaborate with him in an extensive cultural analysis of black Harlem (Blair, 33).

Harlem Document is a compilation of fifty-two photographs of Harlem and its residents taken in the 1930’s. The book is divided into five sections: Harlem’s businesses, children, religious and social organizations, entertainment and culture, and domestic life. Included in the document are interviews with Harlem residents, performers, shopkeepers, as well as children’s street rhymes and photographs of prostitutes. The loose narrative woven by the images moves from street to more interior, domestic settings, which brings the looker further into the Harlem community (Entin, 357).

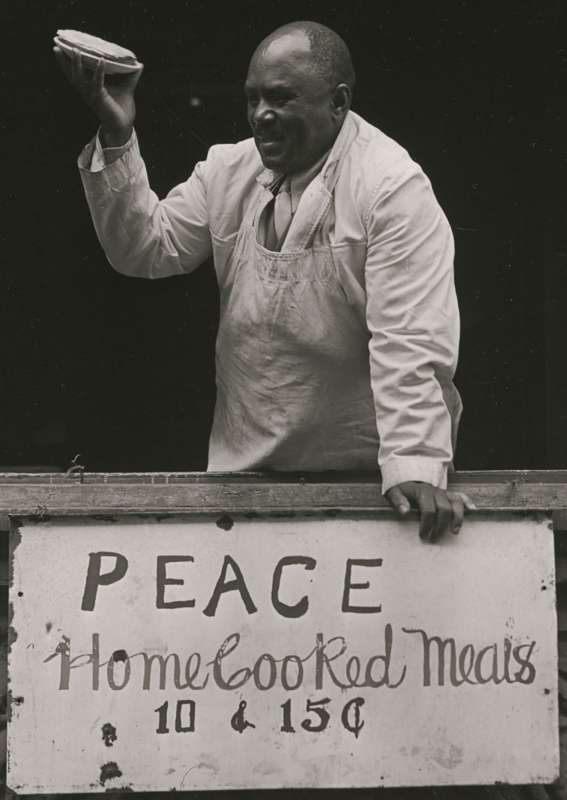

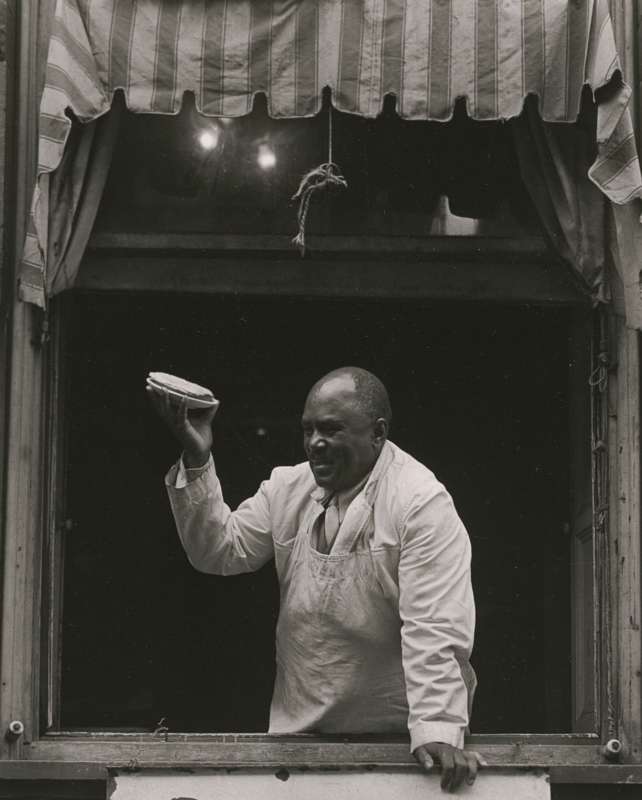

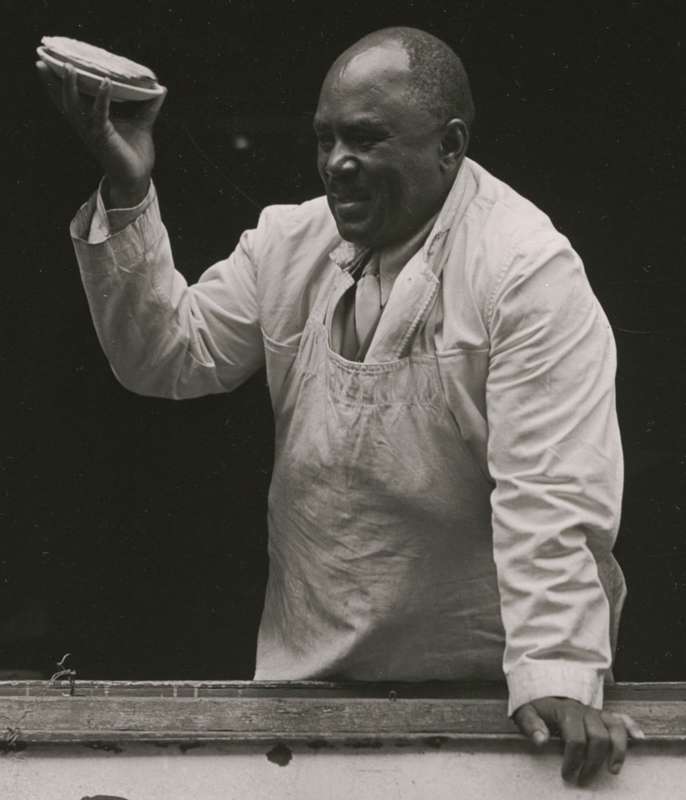

Peace Meals from a Harlem Document features an aproned man leaning out of an oversized window. He holds a pie in the air and gazes at an unseen object outside of the frame of the photograph. Hanging below the window is a sign that reads, “Peace Home Cooked Meals 10 & 15¢”. Siskind shot the image from a distance and with a flattened depth of field. The specific details of the man’s clothing, the rugged quality of the peace sign, and the texture of the stone facade of the building are all equally in focus.

Harlem residents would have readily recognized this individual as a follower of the popular local evangelist, Father Divine. The charismatic Divine hosted “Holy Communion Banquets” in his home that doubled as worship services. Members, who believed their leader was divine, would offer praise to Father Divine with song and dance. During the Great Depression, Divine and his followers opened a network of farms, grocery stores, and hotels to feed thousands of Americans (Dumenil; Father Divine).

At the same time, there is a certain caution which is captured via the camera’s approach. The framing of the railing is slightly blurred, which marks an aspect of separation of the viewer from the subject. Likewise, the posture of the subject blocks the satisfaction of the viewer being directly addressed: the man denies the viewer his complete frontality and we are forced to accept only his profile. In this way, the subject claims back his narrative from the photographer and viewer as the lens prohibits any control of the man's gaze.

As the subject lifts the pie - a symbol of Harlem’s spiritual and entrepreneurial culture - he seems to emerge from the interior. As he offers up the pie, he also offers an image of black self-determination - but not for the viewer or for the photographer. Siskind’s composition of the image marks a respectful distance from the world and experience it captures.

Following the civil unrest related to the events of the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, I saw firsthand the importance of avoiding projecting my own white narrative onto the events taking place. I am a native of Louisville, Kentucky, which was the home of Breonna Taylor. As my black friends began getting involved in peaceful protests, I realized how important it was for them to lead their own fight, and more importantly, to frame their own conversations.

My friends discussed with me how hopeful they were that so many white people were turning out for peaceful marches. However, I know many of them had to have difficult conversations with white activists who hadn’t yet confronted their own attitudes about race. In a culture that is white dominated, it was clear to me that many white people who wanted to do good in this fight for justice did not necessarily want to be led by a black person. White participation often resulted in the narrative being written by white people through the media. Rather than have their white counterparts show up for the Instagram picture, my friends wanted whites to show up because they understood the greater risk a black person has of being killed just because of the color of their skin.

This piece by Siskind was important to me in reflecting this sentiment. Although the photograph was captured in the 1930’s, Siskind still understood the difficulty in capturing this specific community from Harlem in which he didn’t share a similar social landscape. Rather than attempting to reflect his own culture and opinions through the lens, Siskind chose to keep his camera detached in a way and capture the subject as he was looking into the distance - prompting us as viewers to ponder the fact that as a white image maker, Siskind was unable to force his whiteness onto this act of self-representation.

As an ally, it is my job to stop leaning on my privilege. Like Siskind, I can be a witness to this culture which begs to be recognized and respected without overwhelming the fragility of the grassroots movement being built by black leaders during this time of civil unrest. It might mean listening more often, and it could lead to making some mistakes. That simply means there is more work to be done. As a white ally, I can’t claim any of this movement for justice as my own. All I can do is support the fact that black lives do matter.

Madelyn Steurer

Class of 2022, Master of French and Francophone Studies

Blair, Sara. Harlem Crossroads : Black Writers and the Photograph in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Dumenil, Lynn. "Father Divine's Peace Mission Movement." The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Social History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Dixon, Vince. “The Depression-Era Cult Leader Who Fought Segregation Through Food .” Eater.com. Eater, October 29, 2018. http://www.eater.com/a/father-divine.

Entin, Joseph. “Modernist Documentary: Aaron Siskind's Harlem Document.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (1999): 357–82. https://doi.org/10.1353/yale.1999.0014.

Siskind, Aaron. Aaron Siskind : Toward a Personal Vision 1935-1955. Chestnut Hill, Mass.: Boston College Museum of Art, 1994.

Yochelson, Bonnie. “Interview with Aaron Siskind,” taped interview with Siskind, conducted by Bonnie Yochelson for Charles Traub’s photography class at the School for the Visual Arts, New York City, February 1988.